WereUAt: Location data re-identification from theory to practice

Rédigé par Cyril Miras

-

02 août 2022The LINC has obtained a geolocation database from a data broker which was said to be anonymized. In order to experiment and test the anonymization criteria, the LINC has initiated a project evaluating the risk of reidentification starting from this pseudonymized data. It will then try out anonymization methods intended to limit privacy risks for users while ensuring the data can still be used.

What is the project about?

The issues around geolocation data

Smartphone geolocation data is useful to a number of digital stakeholders: it can be used in many different contexts, to fight an epidemic or optimize road traffic, but also to track users for advertisement purposes or behavioral surveillance, and many other applications. The LINC wondered, in its 2017 IP Report, “La plateforme d’une ville” - The platform of a city (p.32) if geolocation data was “new sensitive data”: “geolocation and data flow are to personal data what stem cells are to cellular biology: “totipotent”, they allow, by their abundance of context to infer a considerable amount of data about behavior, habits, and lifestyle. Knowing where you live may allow someone to infer your income, where you go, to guess your lifestyle (hobbies, family circumstances…), your religious habits or sexual preference, even your health situation”. To give an example, researcher Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye demonstrated, as soon as 2015, with a study on a credit card dataset produced over three months by 1,1 million people, that just four “spatio-temporal” points (geographical coordinates, date and hour) are enough to uniquely identify 90% of the individuals. This trove of information is coveted by data brokers specialized in the collection and resale of geolocation data, which is even more valuable as it is abundant and precise.

However, the ambition to collect and sell extremely precise data raises the question of personal data protection for the people who contribute - often unwittingly – to these datasets. In fact, in some cases, companies have eroded user confidence by reselling geolocation data collected from children, people visiting abortion centers, or by publicly outing a person’s sexual orientation. In the European Union, geolocation data associated directly or indirectly to a person is considered to be personal data. Data processors thus have to respect strict rules regarding the processing of this data as well as the rights of the people whose location is collected.

The geolocation data market: a press review

In February 2021, the company Predic.io was singled out for sharing geolocation data from users of the app “Salaat First” (a prayer application) to a company that sold it back to a US federal agency. As a result, applications using the Predicio SDK were banned from the Play Store.

In early July, the Danish media outlet TV2 claimed it had bought geolocation data of 60 000 smartphones for 4 800 euros.

At the end of July, newspaper “The Pillar” obtained Grindr geolocation data of priest Jeremy Burrill and used it to reveal his sexual orientation. This news was covered in the LINC’s website and motivated a study of this ecosystem.

In September, the journal “The Markup” published an investigation on the geolocation data market. It shed light on the role of a number of data brokers.

In October, the website Vice indicated that a data broker sold data collected without user consent. After that publication, in December, Google ruled that applications using this SDK needed to ask for user consent or face being excluded from the Play Store.

On December 6th, 2021, the Markeup revealed that family protection app Life360 sold the geolocation data of its users without using an SDK (it sold directly the data it collected).

On April 11th, 2022, John Oliver dedicated his TV show, Last Week Tonight, to data brokers. He discussed several problematic cases of personal data resale was problematic in the US and demonstrated it was possible to reidentify political leaders quite easily using data bought online.

Anonymization or pseudonymization?

Data anonymization, which consists of processing the data to make it impossible to reidentify one person in particular, allows for it to be shared while being respectful of privacy and personal data rights. As a matter of fact, sharing anonymized data allows one to be released from GDPR restrictions, as it is no longer personal data. Numerous techniques promising to share information sourced from geolocation data while reducing privacy risks have been proposed, and several examples are cited in the scientific reviews dedicated to the topic. However, no privacy-protecting method is able to keep the utility of the original data intact while eliminating the risk of reidentification. Therefore, a compromise must often be made between the privacy guarantees offered by the existing techniques, and the utility of the data for the computation of a specific task.

Pursuing another goal, de-identification, which merely consists of replacing directly identifiable information in a dataset (such as name, surname, social security number etc…) with indirect identifiers (in the form of numbers or a different name), is also used to limit risks linked to personal data processing. But unlike anonymization, de-identification methods are not irreversible, and it is sometimes possible to reidentify individuals using additional knowledge. As a consequence, de-identified data is still personal data, and one must be GDPR compliant in order to process and share it!

In some cases, this risk came true and some people were reidentified in publicly accessible datasets, in Melbourne or New York. Following up with that last example, in which several American celebrities were reidentified, the LINC illustrated, in the 2017 CabAnon project, how different privacy-protecting techniques could be applied on public data. Our project aims to pursue this research, and apply it to the case of location data that is being sold online.

Project goals

This project aims to test with a concrete example, and as the case may be, demonstrate, the risks of reidentification posed when a data broker sells deidentified geolocation data. In doing so, we set out two goals: first, to increase public awareness about the risks posed by personal data sharing; and second, to demonstrate that further privacy-protecting methods are necessary to provide proper confidentiality guarantees and meet legal requirements. This study builds on one of the priority topics for investigations set out in 2022, as the CNIL will “check the compliance with the GDPR of professionals in the sector, in particular those who resell data, including the many intermediaries in this ecosystem (also called data brokers)”.

Through this project, the CNIL is also looking to improve its understanding of the geolocation data collection and distribution channels through mobile apps, and of the methods enabling individual reidentification from a geolocation dataset as well.

Which data will be used?

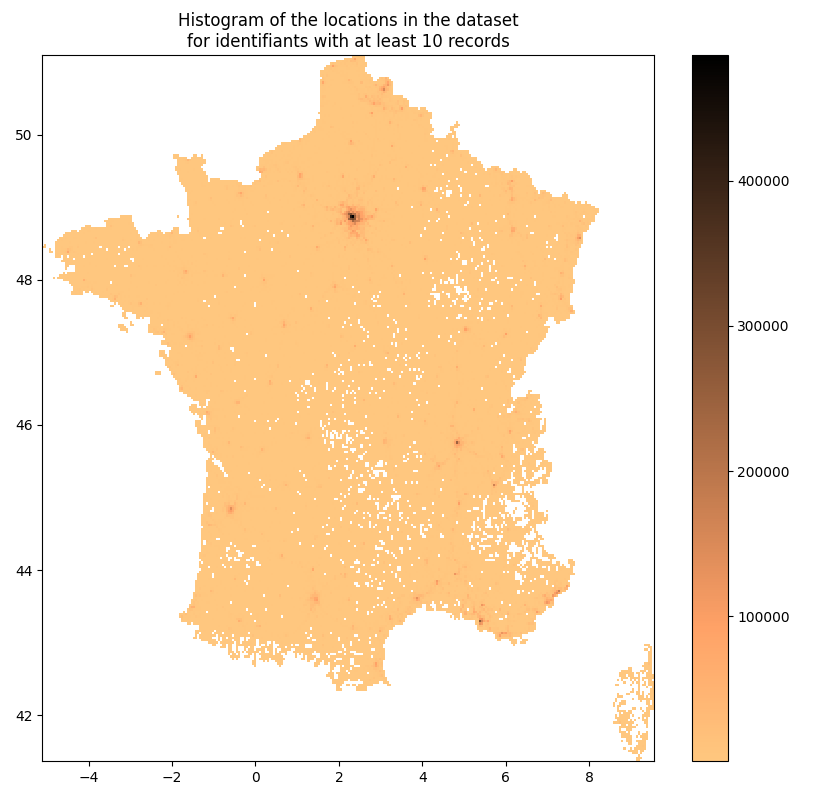

The database obtained by the LINC contains around 100 million geolocation points situated in metropolitan France, collected over a week (October 8th to 15th, 2021), and concerning 5 million unique identifiers. This is a free sample obtained from a data broker that offers a subscription-based access to its database for a few thousand euros a month. Names and surnames are excluded from the base as well as other directly identifiable data, although it still includes the advertising identifiers of the users whose data is being sold. In application of the minimization principle of the GDPR, we filtered the data in order to keep only identifiers with 10 or more geolocation points in the dataset.

Further reading

Photo credits: Pixabay