1970-2021: Data protection spreads the world

Rédigé par Jeanne Saliou

-

27 octobre 2021The number of data protection laws around the world has increased considerably over the last two decades. In this context of normative growth, the LINC questions these developments. What are the drivers of this legislative dynamism? At what scale(s) can they be fully understood?

[Dossier] Data protection and privacy around the world

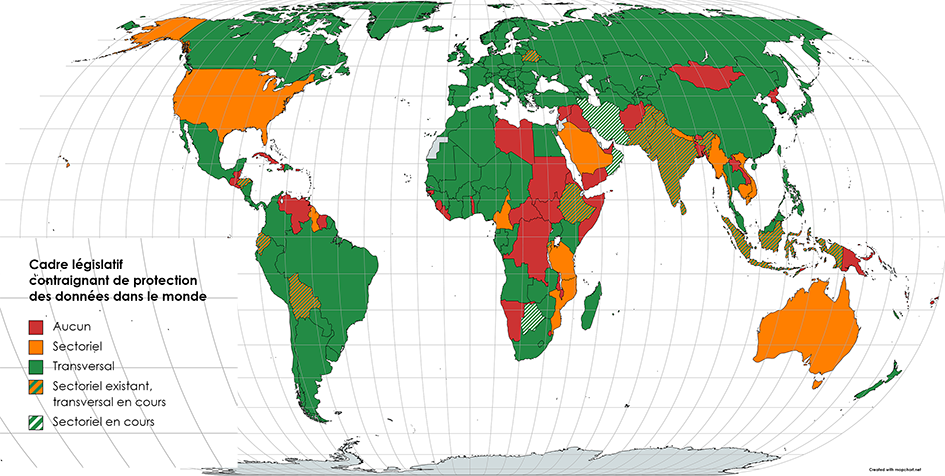

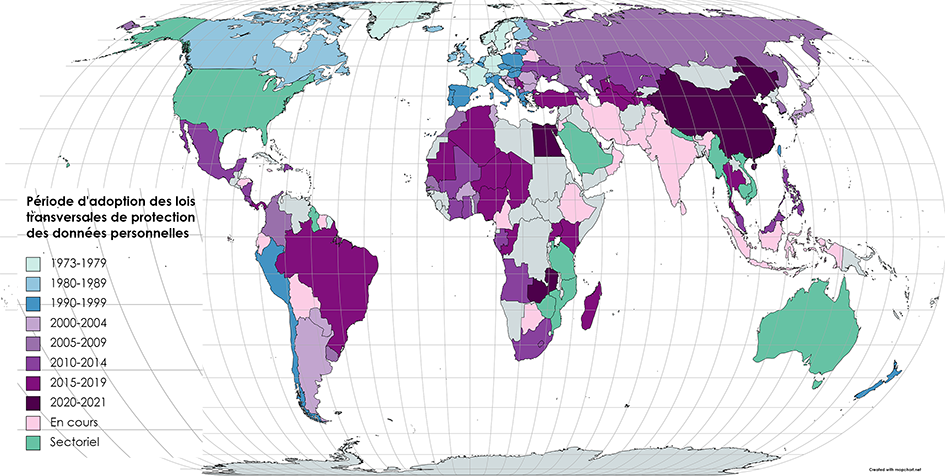

In recent years, data protection has undergone considerable legislative development around the world. In the space of a decade, the number of cross-cutting national laws - applying to all sectors of activity, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union - has almost doubled, from 56 countries covered in 2009 to 106 in 2020. This number is expected to continue to grow, with 25 states having bills in the pipeline. And this does not include states that have data protection provisions within sectoral legislation - limited to a particular industry – or specific legislation – relating to a restricted category of the population. Examples of these two types of legislation can be found in the United States with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 focusing on the health sector and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 regarding the privacy of minors.

At a time when the data economy is developing, this multiplication of applicable legal frameworks has many consequences, both for individuals - who gain rights and increased protection - and for private entities. Indeed, the latter are dependent on international agreements when their activities involve transnational data transfers. The European Union can issue an adequacy decision to certain non-EU countries so that they no longer require specific authorizations for transfers. The invalidation of the Privacy Shield by the Court of Justice in Schrems II case, led to many difficulties, illustrating how the convergence of data protection laws has become a major issue for economic exchanges .

Therefore, one can wonder about the trends that are emerging in the international data protection landscape. Are we moving towards a standardization of legal frameworks on a global scale? If so, is this a complete harmonisation, of texts and their implementation, or is it window-dressing?

To better understand the global evolution of data protection in the long term, and thus to anticipate potential pitfalls in terms of cooperation, the LINC proposes to review the historical and geographical development of data protection, before studying other aspects and issues of this legislative boom.

The development of data protection around the world

From Big Brother to « surveillance capitalism »

A quick look at the legislative landscape of data protection highlights a general shift in concerns from the 1990s onwards, from legislation focused on public actors to regulation of data use by private ones. Whether in the context of the French Loi Informatique et Libertés of January 6, 1978, or the Israeli Regulations on the Conditions of Possession of Data by Public Entities of 1986, attention was mainly focused in the 1970s and 1980s on state registers and other public databases. And for good reason: after the use of national registers for deportation purposes during the Second World War, particularly in France, national files had bad press and confidence in the State was more than eroded. The prospect of the creation of digitized files and their interconnection was worrying. Especially since, as Peter Swire and Robert Litan have pointed out, the Internet was still an experimental system used mainly by certain governmental agencies and the research world in those years.

However, files held by private entities were not ignored by the lawmakers of the time. From 1971 to 1974, a committee was set up in Norway to study the uses of data in the private sector, particularly by credit rating agencies, in parallel with the committee that analyzed public registers from 1972 to 1975. The Personal Data Registers Act adopted in 1978 thus covered both the public and private sectors. Similarly, in France, the Loi Informatique et Libertés extended the guarantees provided for the management of public registers to those of the private sector in 1978.

The Australia Card and the 1988 Privacy Act

In 1985, the idea emerged in Australia to create a national identity card, the Australia Card, to combat tax and welfare fraud. After some time of little attention, the measure led to an unprecedented media uproar, culminating in September 1987 with more than one demonstration per day, and leading to its withdrawal by the government shortly after.

As a result of this public debate, a political compromise was reached involving, on the one hand, the creation of a system of tax file numbers, thus limited to the field of taxation, and, on the other hand, the adoption of the first piece of legislation on the protection of privacy, the Privacy Act of 1988.

Source : Greenleaf, G. (2008). « Privacy in Australia » in Rule J and Greenleaf G (Eds) Global Privacy Protection: The First Generation, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

From the 1990s onwards, the development of the information society and the Internet brought about a tangible change in priority: the regulation of private databases, which had previously been done at the margin, became the main source of legislation. During this period, personal computers and the Internet became widespread. From 213 registered computers on the Internet in 1981, the number of users worldwide reached 300 million in 2001 according to Barry Sandywell, a professor at the University of York . If for individuals, the development of uses has been heterogeneous on a worldwide scale, companies and especially the largest ones quickly adopted them. From then on, it was no longer so much the concentration of information in single registers, but its dissemination that was worrying, especially due to the dissolution of the frontier between public and private space and the potential intrusions and leaks that resulted from it. As Barry Sandywell pointed out, the risks associated with technology became "democratized" along with it. Everyone was now exposed to viruses, online fraud, and email spam, and with the proliferation of private databases, the possibility of having one's data leaked as part of a cyberattack also increased.

The growing consideration of the private sector has been reflected in the inclusion of data protection provisions in the laws governing certain sectors of activity. The 1999 Law on Banking and Financial Institutions in Cambodia is one example of such additions, often representing developments in the need to preserve professional secrecy. It established a general prohibition on the disclosure of clients' personal information, except when requested by certain authorities.

The sectors concerned were, and continue to be, generally the same from one country and one continent to another: health, security, banking and finance, telecommunications, etc. And with the development of technologies, new uses to be regulated emerged such as electronic commerce and electronic signatures.

At present, a turnaround is observable in comparison with the 1970s. The private sector now is systematically integrated into the laws, while the regulation of the public sector is more fluctuating. As early as 2012, Graham Greenleaf identified a group of Asian states that exempt the public sector from data protection obligations. It includes Malaysia, Vietnam, India, Qatar, and Dubai . China also confirmed its place in the group with the adoption of the Personal Information Protection Law in August 2021, state activities being excluded from its scope.

A relatively homogeneous development on a continental scale

Data protection laws, especially cross-cutting ones, have been spreading around the world at an accelerated pace in recent years. This development is hardly based on a continental logic. While Europe, particularly under the effects of Community integration, was in the vanguard with a very large number of cross-cutting laws adopted before 2000 and with the adoption of Directive 95/46/EC on data protection, there are only slight similar trends on the scale of other continents. For the rest of the world, it should be noted that few non-European countries adopted such legislation before the year 2000. Examples include the 1994 Peruvian law on habeas data, or the same year, the Korean law on the protection of personal information managed by public agencies. During this period, international standards were also few in number, non-binding or optional for ratification, and carried by organizations such as the OECD and the Council of Europe, with an important European dimension or involvement. On a sub-continental scale, West Africa and sub-Saharan Africa have seen a strong development in the last decade, with the adoption of cross-cutting laws in Guinea in 2016 and in the Republic of Congo and Nigeria in 2019. Finally, Asia appears to be in the midst of a major shift with a large number of laws being passed. Bills are pending in Pakistan and Indonesia, among others.

Various rationales and motives for creating data protection laws

The emergence of sectoral and cross-cutting laws at different times between countries should rather be analysed at national and international levels. After the 1980s, the reasons multiply and overlap without any particular chronological logic, with a growing number of states turning to the European model of cross-cutting laws.

While there is no standard pattern to the process of adopting data protection laws, certain reasons for legislating are recurrent. On the one hand, legislation is linked to the arrival of technologies and the development of their use in each country, or at least to governments' awareness of the impact of these technologies. On the other hand, it also seems to follow common developments on a global scale, such as the scandals and fears concerning state files, or the development of electronic transactions.

Among the reasons for adoption, economic necessities seem to take precedence in recent years due to the requirements linked to international data transfers. These considerations are not new. They emerged as early as the 1990s, in particular with the European Union Directive 95/46/EC establishing the requirement of adequacy of protection standards in the context of data transfers outside the Union. The objective of facilitating the flow of data in Europe was prominently included in Article 1, paragraph 2 of the directive, alongside the issue of protecting individuals with regard to the processing of their personal data. The adoption of this directive came at a time of tension over intra-EU data transfers, following the CNIL's refusal in 1989 to authorize the transfer of data from Fiat's French subsidiary to its parent company in the absence of equivalent protection in Italy. With the development of the data economy, these economic considerations are becoming increasingly important and are encouraging changes in the position of companies with regard to legislative projects. According to Peter Swire (interview with LINC, June 17, 2021), a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, just as the Fiat case in Europe had prompted economic actors to favor a European rather than national data protection frameworks, recent developments at the level of some federal states of the United States could lead the private sector to revise its position on a federal law. The adoption in 2018 of the California Consumer Privacy Act signed the beginning of a fragmentation of the US data protection legislative landscape. It has since been followed by the Colorado Privacy Act and the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act, and more are likely to be adopted. Having to comply with a patchwork of regulations within the country will increase the cost of compliance for companies may favour the emergence of a federal law.

However, prior to and in parallel with this rise in economic issues, the reasons for adoption draw on national political and legal contexts. Some countries, such as Mexico, found themselves held back for a time by the absence of legislative powers in this area or, conversely, by the legal obligation to transpose constitutional provisions previously provided for. The Argentian law of 2000 was born of the need to implement Article 43, which enshrines the principle of habeas data, introduced in the reform of the National Constitution of 1994. In other countries, governments wish to improve their image on the international scene, like in Tunisia (see box).

An issue of international influence - The case of Tunisia

The protection of personal data entered the Tunisian legislative landscape in the early 2000s, when Tunisia was still governed by a police regime. This same regime not only enshrined the "inviolability of personal information" in Article 24 of the Constitution in 2002, but also adopted a law on the protection of personal data in 2004, leading to the creation of the INPDP in 2008.

It is easy to agree that "for a police regime to enact such laws is almost a luxury" (Chawki Gaddes, President of the INPDP, interview with LINC, 8 June 2021). This granting of a right to data protection by Ben Ali's government to the Tunisian population is in fact part of a logic of international influence much more than a desire to improve the protection of citizens. Encouraged by the United Nations to organize the world forum on the information society, Tunisia embarked on a process of modernizing its legislative apparatus, characterized by the creation of numerous laws and national agencies, including Law No. 2004-63 of 27 July 2004 on the protection of personal data.

Thus, behind the international legislative boom, multiple dynamics are at work, which overlap and are layered according to the different states. This diversity at the heart of a shared international trend raises questions about the convergence of the content of these laws, as well as the role of the GDPR in this framework, but also about the uniqueness of the notion of data protection in societies.

Global data protection and privacy framework (in french)

Document listing the different legislative frameworks in the world, as of 1 October 2021. This data is subject to change and has been used to produce the maps included in this article.

1 Swire, P. et Litan, R. (1998). None of Your Business: World Data Flows, Electronic Commerce & the European Privacy Directive, chap. 3 (Brookings). http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/articles/pdf/v12/12HarvJLTech683.pdf

2 Sandywell, B. (2006). « Monsters in cyberspace, cyberphobia and cultural panic in the information age ». Information, Community and Society. Issue 9 :1, pp39-61.

3 Greenleaf, G. (2012), « Global Data Privacy Laws: 89 Countries, and Accelerating ». Privacy Laws & Business International Report, Issue 115, Special Supplement, February 2012, Queen Mary School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 98/2012

Illustration : Giuseppe Rosaccio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons